The late philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn introduced the term ‘paradigm shift’ in his 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. While Kuhn focused the term on major changes in the natural sciences, it has become a popular approach for framing significant shifts in our understanding of business, politics, and other fields. In forestry, as technologies advance and new markets emerge, the question of paradigms feels relevant for those looking to maximize value from timberlands and wood basins.

Forest Carbon

For example, with carbon markets and ESG driving investment pitches and dialogues in Board rooms, do we have a new model of forest management on the table, or do we simply have a new forest product, in forest carbon, that must compete for its “share” of the forest?

From the perspective of a timber investor or, in particular, a firm that owns timberland and mills, the process for realizing value from a given timber market or wood basket is a resource allocation decision specific to the trees grown and harvested from owned forests. This “fact” becomes more relevant in the context of expanding end markets for wood and forests that include CLT and Mass timber on the “traditional” end and ESG or forest carbon markets on the “emerging” end.

Models of Timber Market Management

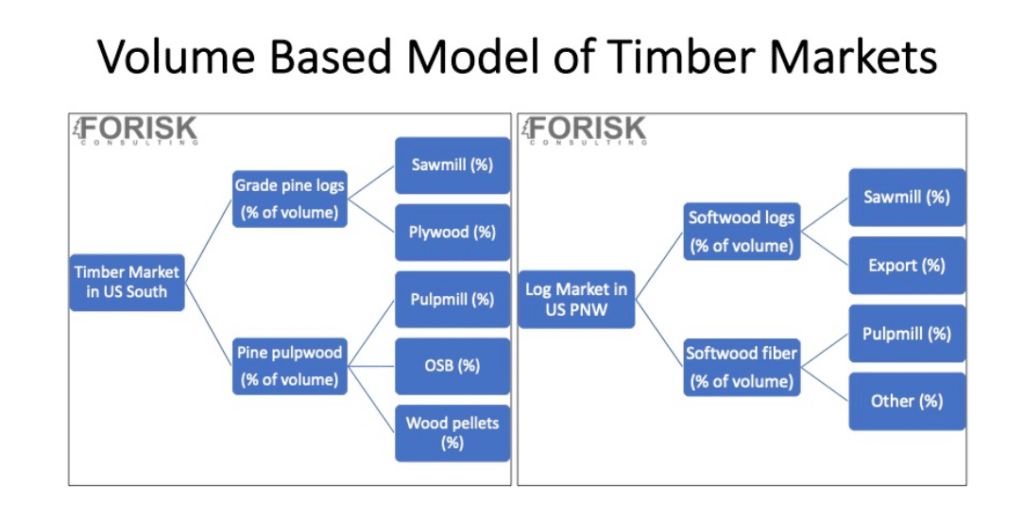

To compare how timberland owners and investors in different geographies might allocate their log resources, consider these basic models for framing timber market fundaments. For traditional timber markets, volume-based scenarios, which focus on maximizing the value of trees grown and harvested given the available local mills, can also be differentiated by specific end market or by log size.

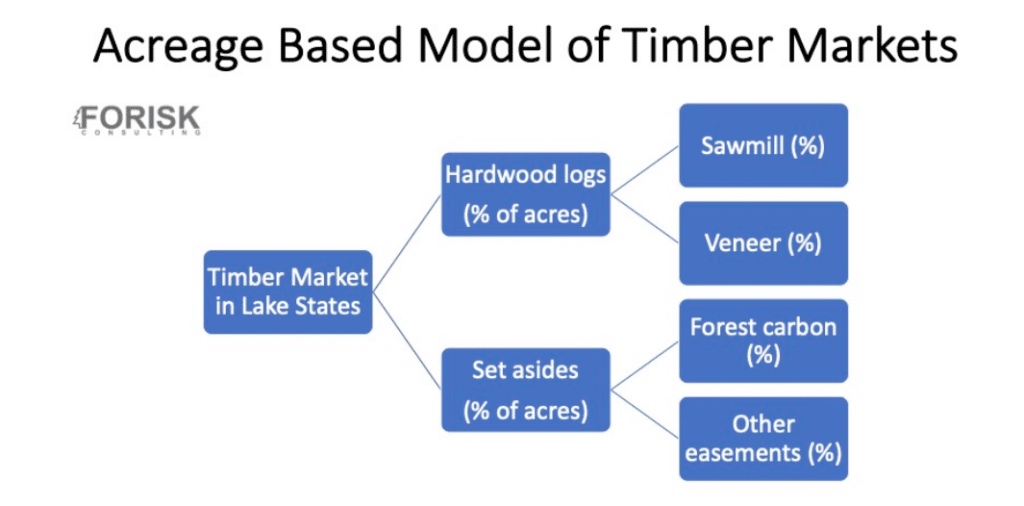

Another way to think about these allocations would be to break up the ownership or markets by acres rather than by timber volumes:

This approach is consistent with the idea of maximizing value per acre. In practice, applied forest management plans reflect volume and acreage hybrids. For example, streamside management zones (SMZs) in all regions comprise acreages pulled out of active operations to buffer waterways or riparian zones, while harvesting activities on the same properties look to optimize log values in the local market.

In the end, we want to avoid building unnecessarily complex models for guiding our forest management and timberland investment decisions. Simply making small new tweaks to older traditional models to account for changes in the market can become hard to maintain or explain. That means step one remains confirming the viability, operability, and reliability of the existing markets for logs and wood. From there, we can explore scenarios to test the implications of new markets.

This content may not be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever, in part or in whole, without written permission of LANDTHINK. Use of this content without permission is a violation of federal copyright law. The articles, posts, comments, opinions and information provided by LANDTHINK are for informational and research purposes only and DOES NOT substitute or coincide with the advice of an attorney, accountant, real estate broker or any other licensed real estate professional. LANDTHINK strongly advises visitors and readers to seek their own professional guidance and advice related to buying, investing in or selling real estate.

Add Comment