One of Georgia’s biggest political scandals involved a massive land sale that had implications for landowners that have lasted more than 200 years. This was a big black-eye for the state legislature and ultimately resulted in the federal government’s involvement in the land sale.

In the 1780’s and 1790’s, after the Revolutionary War, Georgia claimed its territory extended from the Atlantic Ocean to as far west as the Mississippi River. In the late 1780’s, the state legislature began exploring the option of selling some of its western lands to raise money and promote settling in the area. After several failed attempts by land companies to make a successful purchase of the western territories, in 1794 and 1795 some serious contenders came forward. Four separate land companies joined forces to present a $500,000 offer on approximately 35,000,000 acres of land which comprises most of modern day Mississippi and Alabama. This offer of 2 cents per acre was extremely low, even by the standards of the day, but the land companies had U.S. senators, congressmen, and other influential partners that were bent on making this deal happen one way or the other.

Rumors of corruption and bribery began to come forward, and there was a public outcry against the state selling the land to these companies. Another interested company came forward with a strong bid of $800,000 for the property, with $40,000 being deposited as earnest money. This new bidder, the Georgia Union Company, even offered to allow the state to have control of 6 to 8 million acres of the land for public use. But their offer was never given real consideration, and against the best interest and will of the Georgia voters, the state legislators voted to sell the western territory to the four land companies.

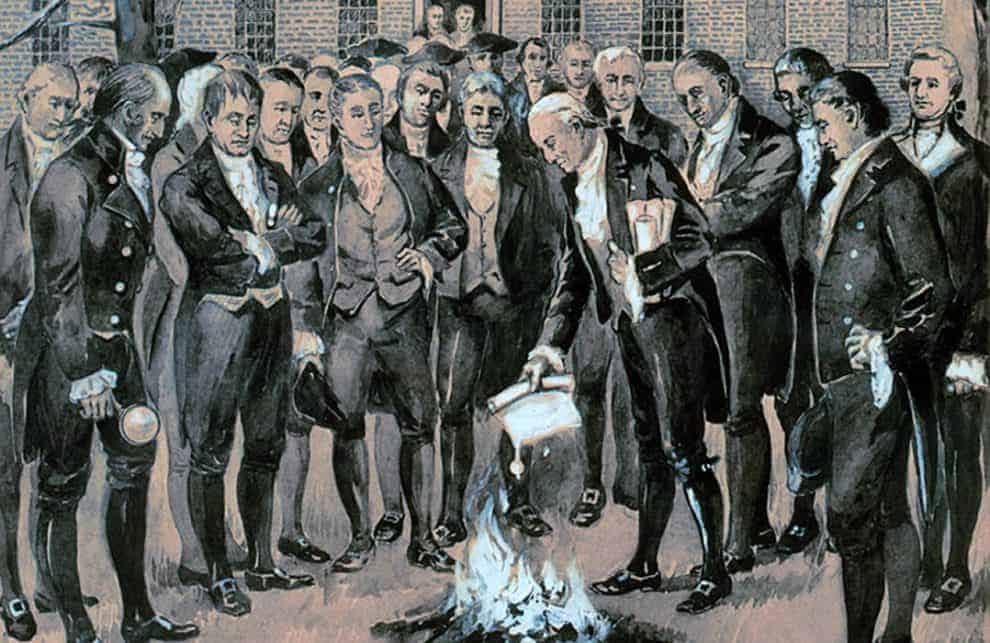

Almost immediately efforts began to repeal and reverse the sale of the western territory. But the four land companies wasted no time in selling parcels to land speculators and investors, who in turn sold to others at a significant profit. In 1796, U.S. Senator James Jackson, backed by then Governor Jared Irwin, signed the Rescinding Act that attempted to invalidate the transaction. Immediately law suits sprang up from the purchasers and others involved with the Yazoo Sale (named for the Yazoo River). The lawsuits continued until one of the cases was eventually heard by the Supreme Court in 1810. In Fletcher v. Peck, Chief Justice John Marshall rendered an opinion that the Rescinding Act violated the right of contract unconstitutionally.

The United States Congress eventually agreed to buy the property from Georgia for $1,250,000, and in 1814 agreed to pay the damaged claimants $5,000,000 from the subsequent sale of the Yazoo lands. This sale was such an egregious display by the Georgia legislature that a new method to dispose of state-owned lands was devised. Six subsequent land sales were done by a lottery based on a point system to prospective buyers, and many of the parcels were sold at 4 cents per acre.

This is a very fascinating story about the sale of such a large parcel, and it encompassed millions of acres of land and impacted thousands of private landowners. It is interesting how this one transaction had ramifications federally for contract law, the right to rescind contracts, the federal government’s right to invalidate a state law, and other land-related issues. One of the terms of the contract was that the federal government would remove the Indians from the state-owned lands. One of the other terms of the contract eventually led to a brief war between North Carolina and Georgia.

This was a complex and interesting part of the South’s heritage. It is definitely worth a closer study for those who are interested in land transactions. Some of the original documents related to the Yazoo Land Fraud were available online at the Georgia Archives.

This content may not be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever, in part or in whole, without written permission of LANDTHINK. Use of this content without permission is a violation of federal copyright law. The articles, posts, comments, opinions and information provided by LANDTHINK are for informational and research purposes only and DOES NOT substitute or coincide with the advice of an attorney, accountant, real estate broker or any other licensed real estate professional. LANDTHINK strongly advises visitors and readers to seek their own professional guidance and advice related to buying, investing in or selling real estate.

Add Comment